The Rocketship Fallacy

Most startups aim for exponential growth. The usual metaphor is that startups should be a “rocketship”, blasting off into space with rapid growth.

In this post, we argue that the rocketship is extremely misleading for most startups as it only represents the late stages of exponential growth. This can lead them to poor, and fatal, decisions.

Here’s what the exponential growth curve looks like from the beginning. For a long time, it’s not exactly surging growth - it actually looks, and feels, more like a flat line. You need to get comfortable with this period, given that it usually takes years to reach product-market fit (PMF). Aiming for rapid growth without PMF isn’t sustainable and is a leading cause of startup failure.

The Rocketship vs The Snail

Founders are told that a startup should look like a rocketship: a short period of calibration, followed by surging growth and eventually reaching the stars! However, they often feel the need to show surging growth from day one - usually years before it’s realistic. And real rockets take years of testing and “figuring things out” before they launch.

Why is pretending to be a rocketship too early dangerous? Feeling the need to show rapid growth leads to common mistakes that kill startups, such as:

Ramping up marketing spending. Often the quickest way to grow is to buy customers with ads. But as a startup without an established brand, you’ll likely lose money, as CAC > LTV, on each new customer.

Hiring impressive-looking staff to look like you’re growing. Without a proven business model you’re likely hiring people for roles they aren’t a good fit for. For example: it’s probably not a good investment to hire a sales team before you have a repeatable sales process. This is particularly true if you need to pivot, in which case you may have hired for roles that no longer exist.

Spending on unnecessarily scalable systems. Developing complex systems that can support thousands, or millions, of customers is what startups on a rocketship trajectory need to do. But when you don’t even have one customer, is a state-of-the-art Kubernetes cluster really the best use of time & money?

Being dishonest about where you’re at. Pretending to potential customers, employees and investors that you’re a rocketship can lead to bad advice. Even worse, it stops you from getting the help that genuinely fits your stage.

Rather than feeling like your startup should be a rocketship, we propose a different identity: the snail. Snails are better suited for traversing the long period of slow growth before PMF. They’re less likely than rocketships to blow up when things aren’t going to plan, like the market not wanting your product. Instead, snails can correct course when they hit obstacles. Their hard shell also comes in handy, given that 90% of startups are crushed before liftoff.

The 1/10/100/1000 Framework

When everyone tells you to be a rocketship, how can you get comfortable as a snail? The answer lies in measuring progress more sensibly, accounting for the true nature of exponential growth.

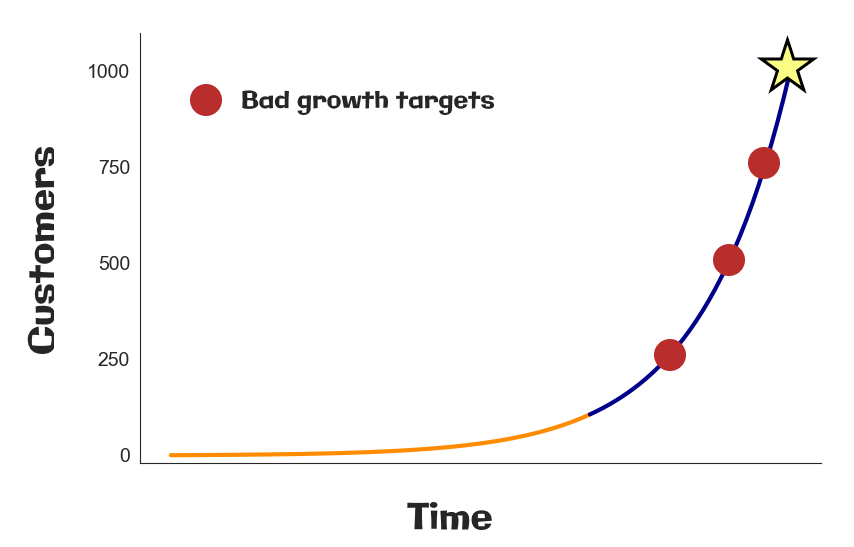

Suppose a startup has 0 customers, and it has a goal to reach 1000 customers. Perhaps this allows it to break even, or raise its next funding round. If we measure progress classically, the startup has to reach 250/500/750/1000 customers to make it 25%/50%/75%/100% of the way to its goal. When you have 0 customers, 250 feels an awfully long way away.

But if growth is exponential, the startup should instead set its goals as 1/10/100/1000 customers. This more accurately reflects its true progress. It’s also better for morale: getting your first ten customers, as a startup without a track record or brand, is really hard. But that’s because you’re actually halfway to 1000 customers, assuming exponential growth, rather than 1% of the way there. Recognising your true progress will help you get comfortable with slow-seeming initial growth.

The 1/10/100/1000 framework only works if you set the right metric. Ideally, this should be as close as possible to “customers who’d be very upset if they lost your service”. Other common metrics, like “website visitors” or “active users”, are unfortunately too easy to cheat. We’ll discuss choosing metrics in a separate post.

Focusing on What Matters Most

Setting your goals exponentially, rather than linearly, helps focus your startup on the right things. Recall that goal of 1,000 happy customers: getting there feels daunting when you only have one (or zero). The to-do list for getting to 1,000 may look something like this:

Acquire 1,000 customers with scalable, cost-effective customer acquisition based on digital marketing

Develop low-friction customer onboarding process so they know how to use your service

Hire customer service team to handle their issues

Delight them by hiring developer team to automate all the needed features

Hire architecture team to make sure the features are all scalable

etc…

This list doesn’t change much if your goal is 250 customers, rather than 1000. But if your next goal is just 10 happy customers, this list may look much less daunting:

Acquire 10 customers (likely by speaking to people you know)

Delight them by servicing their needs yourselves

Build the minimal software needed to help you service them

You’ll be less worried about building fancy systems that no one’s paying for, instead focusing on finding someone who will pay for your service. You’ll realise you don’t need the latest GPT integration to delight them. In fact, you may not need much software at all! By serving customer needs yourself, rather than with software, you’ll also learn firsthand about how to better design your product.

Wrapping Up

If startups need to grow exponentially, they should measure progress exponentially. This means they go through a long period of very slow growth at the start. They need to get comfortable with this period, which feels more like being a snail than a rocketship. Startups feeling they need to show rapid early growth leads to big mistakes, like running loss-making ad campaigns before they’ve learned how to sell their service 1-to-1. These mistakes can be fatal, making their “rocketship” explode.

Measuring progress with the 1/10/100/1000 framework gets startups more comfortable with seemingly slow growth early on. In turn, this helps them focus on the right things - finding customers and delivering a great service - rather than building fancy systems that may never get used. If they do this consistently, they’ll get more and more happy customers… so the snail might just board the rocketship.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this post, you might like to hear about our personal experience running a fitness-tech startup. You can read our story here.